This is not a book to pick up and be enraptured by a beautiful machine; Nichol approaches the book as a journalist and tells the stories straight.

Tales of horror and carnage are told in the same tone as tales of carnal lust (in the Lanc factories, where, to coin a phrase, never did so many women owe so much to so few chaps). Nichol might write in this style – and I’ve not read any of his other books – but he is conscious of the Lancaster’s role in life: a machine of death. Its aim was to ferry bombs over Germany to kill people below on the ground; if its human crew perished, the plane didn’t care and B for Billy would be waiting in the wings if A for Apple ended the mission in a fiery death. Of the 7,377 Lancasters built during the conflict, more than half were lost to enemy action or training accidents. But they were supremely designed for their function.

Nichol has delved into the history books and, more importantly, spoken to the RAF veterans, the people who worked in the factories making the Lancaster – one at Woodford – and people on the ground who either supported, worked with or knew the crews.

Not that you’d know some for long: of the 125,000 men who served in Bomber Command, more than 55,000 were killed and another 8,400 wounded. Some 10,000 survived being shot down, only to become prisoners of war. Aircrew had only a 40% chance of surviving the war unscathed.

His dry delivery is effective when tales he tells stop you in your tracks; it’s the reader that pauses for thought, as Nichol tells the story drily and factually. The two that made me pause (and think about afterwards) were the people who dealt with dead pilots and an idiot who went on a training flight without a parachute.

It’s not something you think about, but when a plane crashed and its crew died, a fresh crew would be in their bunks that same day. It was bad for morale and a bit creepy for the new boys if dead airmen’s stuff still littered the barracks, so as soon as a death was confirmed, every trace of the dead flyer was removed, from uniforms to last letters; the removal men coming in the night and doing their work silently and efficiently.

As for the idiot without a parachute: not so much him as the feelings of his colleagues and as they leapt from the burning Lanc, leaving him aboard. That would be an image that never left you.

Also interesting is the attitude of the RAF to crews of differing ethnicity: there were black and Indian crew members and the RAF bent over backwards to be inclusive, making it clear that any discrimination would be severely dealt with. Would-be Congleton MP and Dambusters hero Guy Gibson seems to have hijacked the narrative somewhat, an unpleasant man who gave his dog a racist name as he was. He was clearly the exception, not the norm, from ordinary flyers up to the high command.

If you’re interested in the war or Lancasters / the RAF this is a good book, with lots of voices of ordinary people from all over the world. Nichol himself is a former RAF Tornado navigator – famously shot down in the Gulf War – and has an empathy for flyers and their planes, without losing sight of the human cost on all sides.

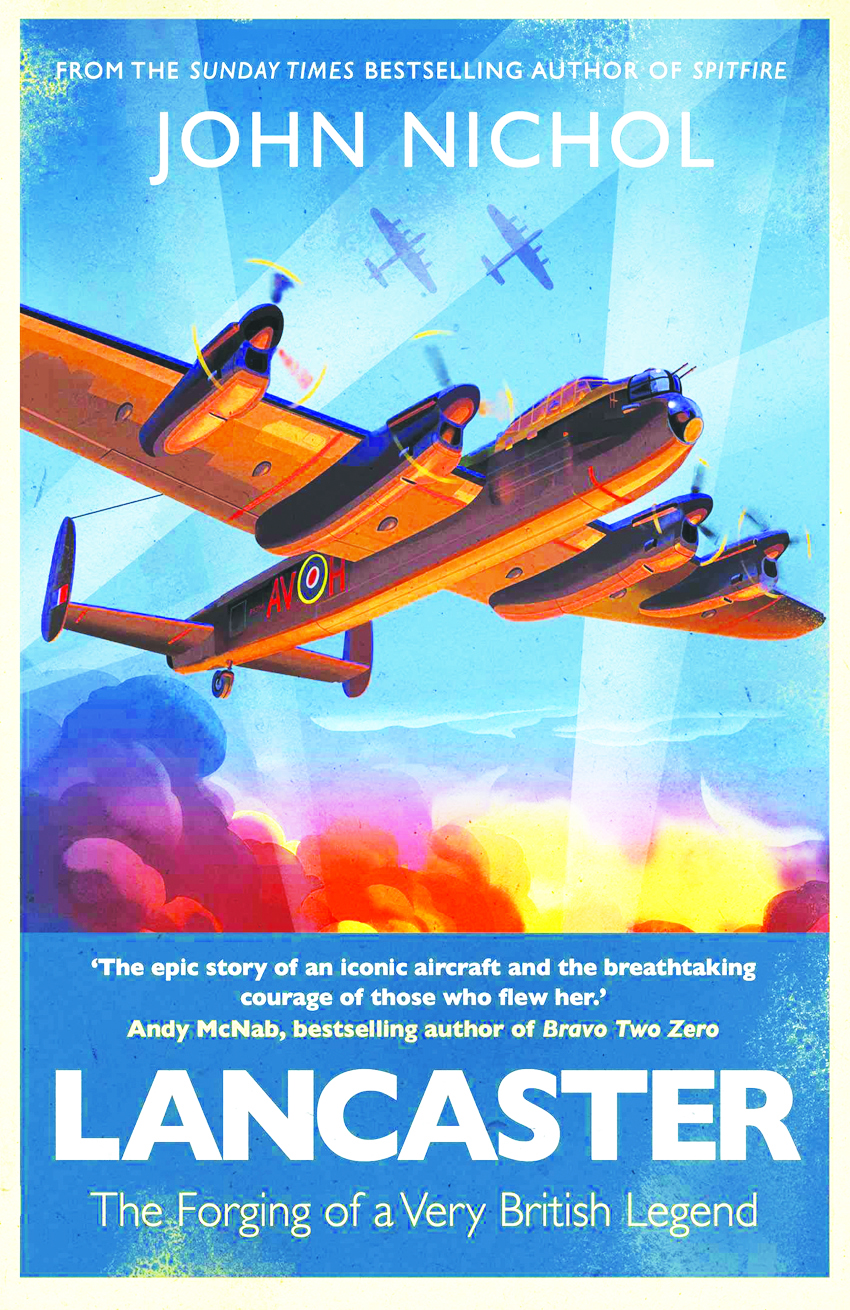

Lancaster: The Forging of a Very British Legend by John Nichol is on sale at the Chronicle, hardback, 464 pages, £20. We can deliver it to your door, free of charge, if you live in our circulation area.

This is not a book to pick up and be enraptured by a beautiful machine; Nichol approaches the book as a journalist and tells the stories straight.

Tales of horror and carnage are told in the same tone as tales of carnal lust (in the Lanc factories, where, to coin a phrase, never did so many women owe so much to so few chaps). Nichol might write in this style – and I’ve not read any of his other books – but he is conscious of the Lancaster’s role in life: a machine of death. Its aim was to ferry bombs over Germany to kill people below on the ground; if its human crew perished, the plane didn’t care and B for Billy would be waiting in the wings if A for Apple ended the mission in a fiery death. Of the 7,377 Lancasters built during the conflict, more than half were lost to enemy action or training accidents. But they were supremely designed for their function.Nichol has delved into the history books and, more importantly, spoken to the RAF veterans, the people who worked in the factories making the Lancaster – one at Woodford – and people on the ground who either supported, worked with or knew the crews.

Not that you’d know some for long: of the 125,000 men who served in Bomber Command, more than 55,000 were killed and another 8,400 wounded. Some 10,000 survived being shot down, only to become prisoners of war. Aircrew had only a 40% chance of surviving the war unscathed.His dry delivery is effective when tales he tells stop you in your tracks; it’s the reader that pauses for thought, as Nichol tells the story drily and factually. The two that made me pause (and think about afterwards) were the people who dealt with dead pilots and an idiot who went on a training flight without a parachute.

It’s not something you think about, but when a plane crashed and its crew died, a fresh crew would be in their bunks that same day. It was bad for morale and a bit creepy for the new boys if dead airmen’s stuff still littered the barracks, so as soon as a death was confirmed, every trace of the dead flyer was removed, from uniforms to last letters; the removal men coming in the night and doing their work silently and efficiently.As for the idiot without a parachute: not so much him as the feelings of his colleagues and as they leapt from the burning Lanc, leaving him aboard. That would be an image that never left you.

Also interesting is the attitude of the RAF to crews of differing ethnicity: there were black and Indian crew members and the RAF bent over backwards to be inclusive, making it clear that any discrimination would be severely dealt with. Would-be Congleton MP and Dambusters hero Guy Gibson seems to have hijacked the narrative somewhat, an unpleasant man who gave his dog a racist name as he was. He was clearly the exception, not the norm, from ordinary flyers up to the high command.If you’re interested in the war or Lancasters / the RAF this is a good book, with lots of voices of ordinary people from all over the world. Nichol himself is a former RAF Tornado navigator – famously shot down in the Gulf War – and has an empathy for flyers and their planes, without losing sight of the human cost on all sides.

Lancaster: The Forging of a Very British Legend by John Nichol is on sale at the Chronicle, hardback, 464 pages, £20. We can deliver it to your door, free of charge, if you live in our circulation area.

Leave a comment